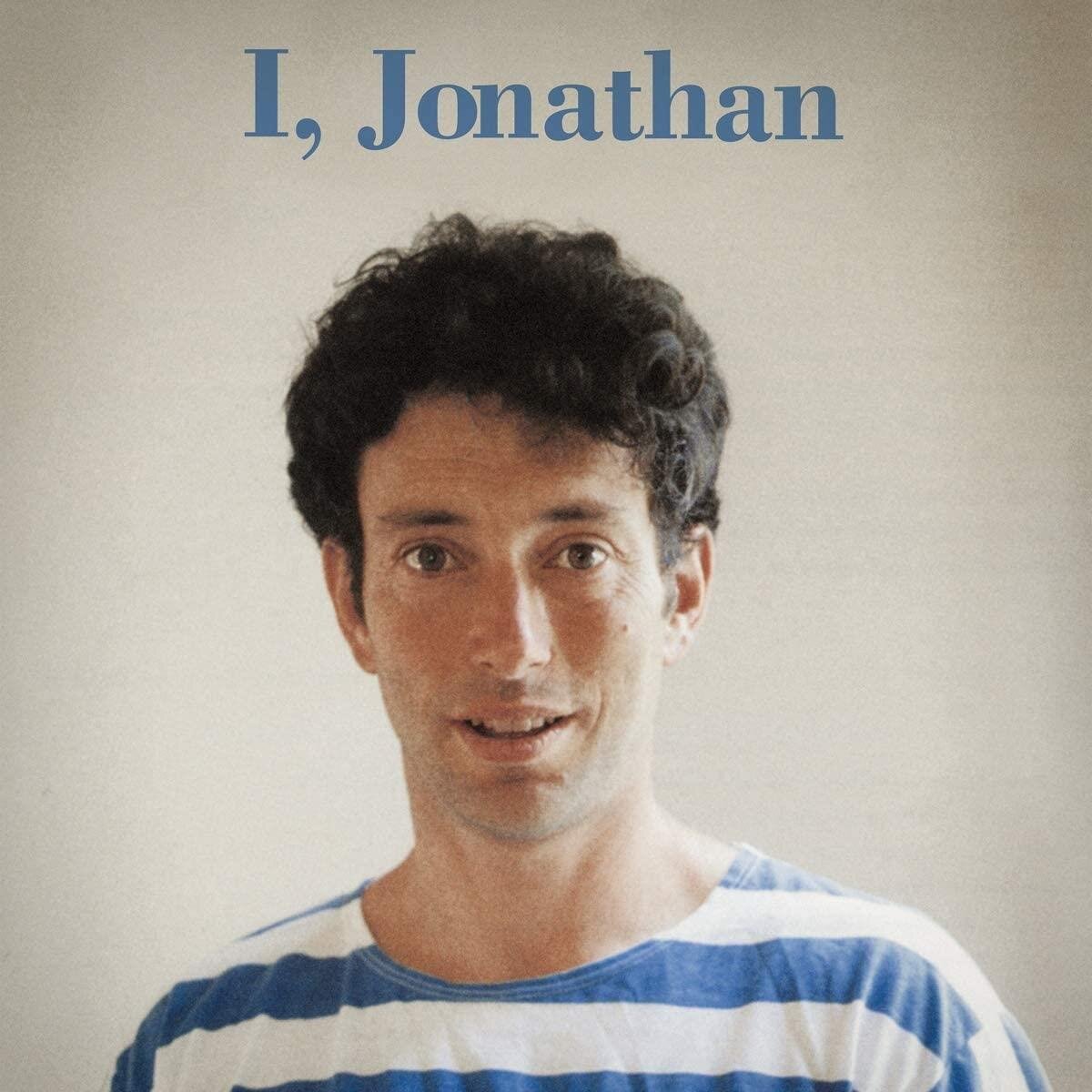

The drive to my guitar lessons is just short enough to be an easy drive, while just long enough to listen to a good chunk of music. Sometimes I enjoy the trip just as much as the lesson. As I headed out one drizzly late July afternoon, I put my recently acquired CD of Jonathan Richman’s “I, Jonathan,” In the CD player.

I couldn’t help but smile as I heard the opening lines of “Parties in the U.S.A.” as Jonathan sang over the dinky but catchy guitar riff and the staccato rhythms of the band behind him: “Well could there be block parties of which I know not?/Wild beach parties around some open flame?/I know there’s got to be parties, I bet there’s a lot/But the USA has changed somehow that I can’t name.” The sounds of the feel good 50s and 60s in the nihilistic and ambivalent 90s. I thought of another one of Richman’s songs while driving, not included on this CD. In his song, “Vincent Van Gogh,” he says, “In the Amsterdam museum I was feeling bad/Been looking for a way not to be so sad/I felt the feeling from the paintings on the wall/And Vincent van Gogh was with me in the hall.” In his own, happy, carefree way, (words almost never used to describe Van Gogh), Richman was doing the same thing for me.

After I had parked my car, I walked into the building and entered the room where my guitar teacher was. He’s a middle aged man with a wise demeanor. The sort that you would have a short but entertaining conversation with at a record shop. I had just finished learning, “Between the Bars,” by Elliot Smith, and hadn’t thought of a new song to learn. So when my teacher asked me what I wanted to play, I found myself saying, with a bit of self-conscious preamble and an embarrassed grin, “‘I Was Dancing in the Lesbian Bar’ by Jonathan Richman.”

My teacher laughed. He agreed in a sort of, “Hey, I’ll teach you that one, sure,” way. He pulled out his phone and pulled up Richman’s performance of the song on Late night with Conan O’Brien; No band on stage, Just Jojo. He watched the video and I watched his face as he saw the video. He reacted at first the way that most people react when they hear Richman sing: Laughter. As we continued to watch the performance, I couldn’t help but smile as Jonathan got more confident and the crowd started cheering and clapping along to the music. We both laughed, though in different ways, when Richman lifted up his guitar and started dancing around on the stage while improvising a wordless melody. He paused the video.

I remember him saying, “Charlie, you’ve got eclectic taste, man.” I wasn’t sure what he meant, so I prodded a bit, just to check. I could tell he didn’t like it. I tried to explain, becoming awkwardly defensive and embarrassed. I didn’t know why this mattered so much to me. I ended by saying I thought Jonathan Richman was a genius. My teacher, in his seemingly endless patience, said, “Charlie, you’re a smart guy. And you like a lot of stuff that I don’t like but I can see the message and the meaning.” (This is in reference to my love of Bob Dylan, who’s voice my teacher hated, but also admired his songwriting) “I would not say this guy’s a genius.” My defense stopped after that. We continued as per normal and I stopped talking and actually started learning the song.

After the lesson I walked back out into the humid and dreary afternoon. I sat down in my car. I turned the radio on and flicked over to the CD function. I felt kind of crushed. Just a few nights before I had shown my family a live performance of Jonathan Richman and they had liked it a lot. We had even talked about who would want to go see him live. As I drove out of the parking lot, The song, “That Summer Feeling” Played. One of Richman’s paradoxically happiest and saddest songs. My guitar teacher’s words were ringing around my head. Why was I so bothered by this? It didn’t really matter, so why get all worked up about it? Richman himself was even quoted as saying, “I don’t really work. I just make things up.” He is aware he is no genius. But he was. To me Jonathan Richman is one of the greatest unsung heroes of modern music. He may come off as naive, or dorky, or uncool, but Jonathan Richman is a true artist and a true rebel.

The first song I heard from Jonathan Richman’s solo career was the aforementioned, “I Was Dancing in the Lesbian Bar.” The song is simple. It tells the story of Richman’s lame and underwhelming experience in a nightclub bar. But, then, some of his friends come and take him to a lesbian bar downtown and he has a great time. It’s a basic song, most would even say a novelty. The humor is unintentionally heightened by the picture of Richman on the album cover and the image it brings to mind of that same man in such a place. But shortly after hearing it, I realized how fun and danceable the song is. Thought about how confident you would have to be to dance in a lesbian bar as a lanky straight guy. Thought about how carefree it must have felt to be dancing alongside Jonathan in that same bar.

This song was my introduction to the world of carefree fun and imagination of Jonathan Richman. I went and listened to “I, Jonathan” and some of his other material. I quickly fell in love with his carefree, joyous attitude. I played him in the car with my family. My older brothers thought he was dorky but liked “I Was Dancing in the Lesibian Bar.” It was one of those great moments that make me love music. Finding those artists that spoke to you that you had never even heard of before. Feeling like they were in some way, a kindred spirit. Wanting to talk to them at a restaurant.

I read all I could about Richman online. I read the wikipedia articles for each of his albums. And I remember encountering a review for the album, “Rock ‘n’ Roll with the Modern Lovers.” The Modern Lovers being the name of Richman’s original group, whose members would change from album to album. The review was from “The New Rolling Stone Record Guide”. The review stated, “[Richman], lost his vision and became once more a teenage twerp … Now you know why everybody picked on that kid in high school.” Ouch. Written with the self righteous contempt of many a Reddit post. I felt strangely offended on Jonathan’s behalf. I thought of this review again when I was thinking about my guitar teacher’s words. Why did this bother me so much?

The 2010s and 2020s have seen a steady increase in, “ironic,” enjoyment of media. Whether this be through watching low quality movies and shows with friends and family, for the intended purpose of mocking it, or through the ever present popularity of, “cringe compilations,” It seems now there are only two ways to watch things: ironically or unironically. Often, this coincides with the popular favor of the media being discussed. If you like something that is unpopular, you can shield it under a veil of ironic enjoyment.

This form of ironic enjoyment is particularly popular among young people, because it has become increasingly unpopular to admit how much you truly enjoy things. This is partially due to the increase in extremely narrow and zealous fandoms which proclaim their love for a particular media with an almost maniacal fanaticism. Apps like TikTok even allow for a person to record their ironic reaction toward the video they want to mock.

None of this is new. This is the latest iteration in a long line of people creating an in-group through the mockery and derision of content they feel is beneath them. And make no mistake, a lot of it is bad. The problem begins when a person becomes critical of everything and is unable to enjoy anything without tearing it to shreds. The object of derision has simply changed from bad TV commercials to sub par internet videos.

Critique has always been a part of internet culture, ever since the very beginning. The early popularity of shows such as, “The Angry Video Game Nerd,” and, “The Nostalgia Critic,” created a market of viewers who didn’t want reviewers to give a fair and honest review of a potential so-so game, but wanted to see wacky caricatures of reviewers abhor a bad piece of media that they are already familiar with.

It’s no understatement that the internet has had a profound impact on the way we look at and digest media. Rather than just simply being given a premade selection of content to choose from, we can instead choose all of the content we could possibly ever need and are even given the power to share our own, blurring the lines between creator and consumer.

In the video, “Critique Culture: Why Can’t We Enjoy Anything Anymore?” by author and Youtuber Robin Waldun, he makes the sobering point that critical lenses can infect the ways we think, and make us become critical of everything that surrounds us, no matter how sincere or or earnest it is trying to be, or how much we do really enjoy it.

As stated before, none of this is new. Comedy and critique necessitate the need of an in-group to laugh at whatever is being targeted. However, the constant moving of the goal post on social media has made people who were previously seen as the voices of reason into the new targets of derision. (This exact thing happened when the aforementioned Nostalgia Critic became the subject of online ridicule and criticism for the mismanagement of his company, and the general awkwardness of his feature length reviews). The Critic becomes the Criticized.

This endless changing of critics was talked about in David Foster Wallace’s “E Unibus Pluram,” in which, Wallace, talking about television, states, “And to the extent that it can train viewers to laugh at characters’ unending put-downs of one another, to view ridicule as both the mode of social intercourse and the ultimate art-form, television can reinforce its own queer ontology of appearance: the most frightening prospect, for the well-conditioned viewer, becomes leaving oneself open to others’ ridicule by betraying passé expressions of value, emotion, or vulnerability.” It seems that any form of rebellion or dissonance from the norm will inevitably become the norm.

In many ways, punk music can be seen as a critical form of music. Punk culture maintains a rejection of established values in favor of a nontraditional lifestyle. Punk’s decrying of everything but itself can be seen as the ultimate form of ironic detached critique.

However, if you constantly say that everyone but you is full of garbage, it won’t be long before people start wondering if you’re full of garbage. Too often, the punk scene has rejected bands for their perceived inauthenticity or for simply, “not being punk enough.” The paradoxical nature of conformity and nonconformity is best summarized by John Lydon (better known as Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols). “Punk became, like, fascist. ‘It has to be this way or else.’…I have always said music should be many attitudes. All are tolerable. It becomes intolerable when one particular form takes over and obliterates the rest.”

A band which was considered a forerunner of punk music just so happens to be Richman’s own Modern Lovers. With their one and only studio album, the band laid down more aggressive garage rock style tracks such as the forlorn wandering of, “Astral Plane,” or the dissatisfaction and frustration of, “Someone I Care About,” mixed in with the detached coolness of, “Pablo Picasso” and “Modern World.” However, in between all of the more angsty and teenage songs of rebellion on the record lie the songs that paved the way forward for Richman.

Fans of Jonathan Richman will notice a conspicuous absence of the song for which many people know him best. “Roadrunner” is, for many, one of the most essential and enduring rock songs of all time. The track sounds simple upon first listen. Over a Velvet Underground inspired riff, Richman talks about the joy he feels when he drives on Route 128 in Boston with the radio on. I remember being fairly unimpressed with the track upon first listen. However, like almost all of my favorite music, it grew on me. In fact, “Roadrunner” has quickly become one of my favorite songs of all time.

The song famously starts with the humorous count off, “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6!” immediately setting it off from other rock songs, with their cliche countdown of, “1, 2, 3, 4!” Richman has stated that bands like The Stooges and the Velvet Underground were major influences on him. He even at one point lived on the couch of the Velvet Underground’s manager, Steve Sesnick. However, unlike the depraved and violent antics of Iggy Pop or the detached indifference of Lou Reed, Richman is completely earnest. There is no hint of irony or self-awareness in his open, wide eyed delivery.

But this is seemingly contradictory to the punk image, right? There’s no anger in the song. There’s no political message or self-righteous venom. So what’s the deal? That’s when you realize. This song is a giant middle finger to negativity and pessimism. This is punk as hell. Rather than conforming to the expectations of the scene, Richman subverts them. The song only has two chords. No need for a third. This song forms the thesis of Richman’s entire career: “Screw you, I’m gonna be happy anyway.” The song is perfect, pure and simple. A stubborn rejection of cynicism as the band flies down the highway, the bass sounding like the purr of the motor, the drums emulating the change in gears, the keyboard infused with the, “modern, rocking, neon sound,” and the final minute’s pure exclamation of joy, the chant of, “Radio on!,” as we feel the magic of the song. By the time the song ends, you won’t have even noticed the nearly five minute runtime.

This is no drug or alcohol induced stupor either, as Richman tells us on the track, “I’m Straight”, in which he sets his happiness apart from the ambivalence of the hippies that were plaguing Boston campuses in the 70s. In this song, Richman rehearses a conversation he wants to have with a girl over the phone about how he thinks that he might be nicer for her than her current hippie boyfriend. Richman’s attitude toward drugs and alcohol is made clear: “Look but, if these guys, if they’re really so great/Tell me, why can’t they at least take this place/And take it straight.” Several years later, this attitude would be adopted by hardcore punk’s, “Straight Edge,” scene, which rejected drugs and alcohol in favor of an alternative lifestyle. This song is also another instance of Richman’s forward thinking.

To give you an idea of how ahead of the curve Richman has always been, all of the songs for the Modern Lovers debut album were recorded in 1971-72, but were not released until 1976. The band broke up after disagreements about the direction of their music. Two of the members, Jerry Harrison, and David Robinson went on to join the bands “Talking Heads,” and “The Cars,” respectively. Richman could have easily used his connections to join a similarly successful band and been a commercial success. Instead, he chose to do something different…

Toward the end of his essay, “E Unibus Pluram,” David Foster Wallace hypothesizes the existence of a new set of intellectual rebellion, after postmodernism had run its course. He writes, “The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point. Maybe that’s why they’ll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. Today’s risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the ‘Oh how banal’. To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness. Of willingness to be suckered by a world of lurkers and starers who fear gaze and ridicule above imprisonment without law. Who knows.” This was later coined by him as, “New sincerity”.

Now, why hasn’t New Sincerity taken hold of American culture and media after being promoted by one of the most popular writers of the 21st century? Well, it seems as if American culture has continued to embrace bitter ironic mockery and pessimism. This seems largely due to the lessons taught by postmodern critique of culture, which were heightened by the Watergate scandal, The War on Terror, The Lewinsky Scandal, and the 24 hour news cycle; all of which were exacerbated by the internet’s critique culture. Americans have been taught, reasonably and understandably, that they cannot trust authority and that they cannot trust anything they are told by the media and press.

This cynicism, however, only breeds misery and malcontent in ourselves. It becomes impossible to enjoy anything, because we’re convinced that it will most likely turn out that we’ve been tricked in some way and that the wool has been pulled over our eyes.

Richman, to me, is the ultimate rebellion against all of this. In his own happy, stubborn, carefree way, he rejects all of this cynicism and instead decides to simply enjoy things as they are. He wants to share his joy with as many people as possible. On his song “Government Center,” he sings humorously about, “ …rock at the government center/Make the secretaries feel better/When they put those stamps on the letters.” A government center is typically a very dingy, sad place to be. But Richman chooses to enjoy it anyway, to live to the fullest and rock on.

Now, I would not go as far to say that Richman was part of the New Sincerity movement. I wouldn’t really say he belongs to any movement. He, like many great poets and songwriters, is a religion of one. This is not a conscious rejection, but rather, a transcendence, in Richman’s case. Richman takes no side in his music. He simply wants to share his feelings with you.

Perhaps one of the greatest culminations of everything wonderful about Jonathan Richman takes the form of an old television recording of him from 1986, live from the Otto Zutz Club in Barcelona. (An out of place location for most artists, but for Richman, he seems right at home). He performs some of his best songs, some of which are still not on spotify, an unfortunate downside of Richman’s obscurity.

The show’s setup is unbelievably stripped down, just Richman and two guitar players. The TV broadcast shows clips from the concert intercut with B-Roll of Richman and of the Spanish countryside, as well as short interviews with Richman himself. After a superb rendition of, “Ice Cream Man,” Jonathan rolls straight into “This Kind of Music,” a song which is very much about himself, in a tongue-in-cheek way. He sings, “I wanna ride my bike to dig the rocking band/I wanna kick my kickstand in the sand/Bass has three strings, they can’t by four/That guitar they got it at the Rexall store/And I want it in my life, this kind of music/That’s the kind I like.” Richman is aware that he is not exactly a compositional genius, but he doesn’t care because he likes what he does. He then ends the song by singing, “That cheap guitar, it’s sounding vile/But it’s so far gone that it’s making my smile”, but before he can sing the final refrain of the song, he stops, singing, realizing that the audience has been singing along the whole time. The look of joy and confusion on his face is priceless, and shows just how much Richman is still young at heart.

During one of the interview segments, Richman talks about his interest in painting. He says, “…before this, what it was, what I was…I liked to paint, with oils. I still do. I like to paint with oils, and I like to paint with watercolor, but when I started with this guitar, I realized that I could do something. When you make a painting, you’re painting, but there are no people around, they see it afterwards. But with songs, and with sounds, I realized that I could go to a place, a night club, and the people would all be there, and I could do something, right then.”

This to me is the genius of Jonathan Richman. Love is the most radical action of all time. As James Baldwin said once in an interview, “Love has never been a popular movement.” The sad truth of modern society is that it’s far easier to simply think of yourself as above everything in your life and simply say, “screw everything,” and try to get on with your life. We say we love people who care but we are never interested in what others really care about, and so they never show it to us. We decide that to care about anything is pointless when it will simply be attacked and picked apart by critics.

And now I have come to realize, that’s what I was so bothered about. For as smart as my guitar teacher is, in that moment to me, he represented all of the cynicism that I saw Richman as rejecting. I love Jonathan Richman. He’s a genius. He means more to me than any of the endless irony and cynicism that our society promotes. Radio on.